A Brief History of Football Kit Design in England and Scotland

© Dave Moor (May 2009)

The Victorian Period (1857-1899)

The game of football is generally considered to date back to the mob football games played in the Middle Ages between rival villages without rules and with unlimited players on each side. The Royal Shrovetide football match is a supposed survival of this early form of the game. Modern scholarship has, however, revealed that small-side games, played by young men according to locally agreed rules, were commonplace and as such, went largely unrecorded.

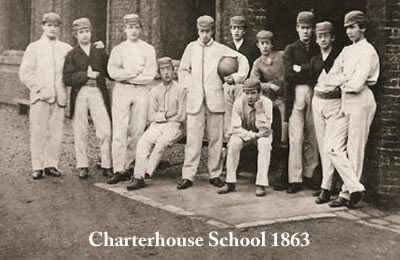

The first recognised rules of football were laid down by English public schools to govern inter-house competition and fell broadly into two groups; the handling game developed at Rugby School and the dribbling game that emerged from Eton, although other schools such as Harrow, Winchester, Uppingham, Shrewsbury, Marlborough and Charterhouse all had their own versions. In keeping with the philosophies of the public schools of the time, these games were extraordinarily violent.

When the young men from these schools went up to university they formed football clubs but games descended into chaos as there was no consensus on the rules. The first attempt to draw up a uniform set of rules took place at Cambridge University in 1848. Although the originals are lost, a set of Cambridge Rules from 1856 survives in the library of Shrewsbury School.

When the young men from these schools went up to university they formed football clubs but games descended into chaos as there was no consensus on the rules. The first attempt to draw up a uniform set of rules took place at Cambridge University in 1848. Although the originals are lost, a set of Cambridge Rules from 1856 survives in the library of Shrewsbury School.

The first football clubs also emerged around this time, most notably Sheffield FC (1857 - the world's oldest club), Hallam (1860) and Notts County (1862). This led to the development of local rules (specifically "Sheffield Rules" and "Nottingham Rules"), which were widely adopted by the newly emerging clubs in the north and midlands. Scotland's oldest club, Queen's Park also developed their own unique code. The majority of games took place within a club, school or university and it took some time for the notion of inter-club matches to catch on. When they did teams might consist of 9 to 18 players and it was common for different codes to be used in the first and second halves.

There were no uniform kits: players would turn out in whatever they had to

hand and teams would be distinguished by wearing distinctively coloured caps,

scarves or sashes over cricket whites (many clubs were formed by cricketers seeking a team game for the winter) or whatever else players had to hand. The first reference to "colours" comes from the rules of Sheffield FC in 1857, which stated:

There were no uniform kits: players would turn out in whatever they had to

hand and teams would be distinguished by wearing distinctively coloured caps,

scarves or sashes over cricket whites (many clubs were formed by cricketers seeking a team game for the winter) or whatever else players had to hand. The first reference to "colours" comes from the rules of Sheffield FC in 1857, which stated:

"Each player must provide himself with a red and dark blue flannel cap, one colour to be worn by each side."

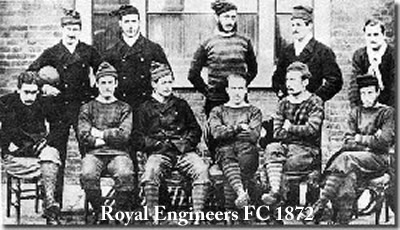

In 1863 leading players formed the Football Association and drew up the first set of national laws of the game, drawing upon the Cambridge Rules and those of the Sheffield Club. Spectators were generally regarded as a nuisance and the game was a robust pursuit for gentlemen from public schools. The leading clubs of the day were formed by old boys of the major public schools (Old Etonians, Old Carthusians etc), by officers serving in the Army (Royal Engineers) and at Oxford and Cambridge Universities.

The introduction of the English FA Cup in 1871-72 marked a turning point as it required all participating teams to play by the FA Rules. Furthermore, the difficulty of telling two teams apart prompted one newspaper correspondent reporting on Birmingham Association's appearance in the FA Cup to write in 1879:

The introduction of the English FA Cup in 1871-72 marked a turning point as it required all participating teams to play by the FA Rules. Furthermore, the difficulty of telling two teams apart prompted one newspaper correspondent reporting on Birmingham Association's appearance in the FA Cup to write in 1879:

"In football it is a most essential point that the members of one team should be clearly distinguished from those of the other. The only way this can be effected is for each club to have a distinct uniform as the diversity of dress displayed yesterday not only confused the members of the team but the spectators were quite unable to say whether a man belonged to one team or the other."

The first uniform kits began to appear around 1870. In England colours were often those of the public schools and sports clubs with which the game was associated: Blackburn Rovers first wore white jerseys adorned with the blue Maltese Cross of Shrewsbury School, where several of their founders were educated. Reading first played in the salmon pink, pale blue and claret colours of the rowing club that spawned them. Caps, cowls and other headgear were de rigeur throughout the decade.

In first FA Cup final in 1872, Wanderers

wore pink, black and cerise while their opponents, The Royal Engineers played

in dark red and navy shirts. The game was played

almost exclusively by men from the upper middle class and minor aristocracy, men who could afford to buy a shirt in their

club's colours from their tailor. That said, plain white shirts were very popular, being both relatively cheap and easily obtainable. As one might expect, given that players bought their own jerseys, there was considerable variation within a team. Early photographs of The Wednesday, for example, show players wearing hoops of varying widths.

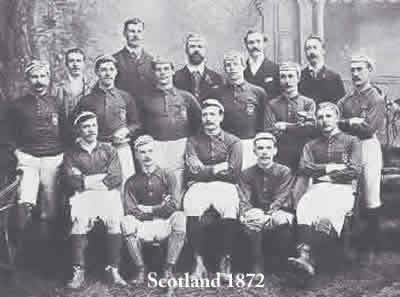

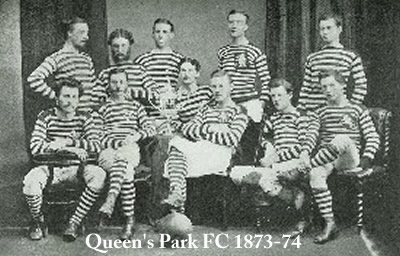

In Scotland the game was pioneered by Queen's Park FC (formed 1867) who affiliated to the (English) Football Association and helped form the Scottish FA in 1873. The Scottish team that played England in the first ever international wore the navy blue shirts of Queen's Park - the club did not adopt their famous narrow hoops until October 1873.

The English game

continued to be dominated by former public school clubs until the early 1880s but in Scotland, association football was taken up enthusiastically by the working

class in the central belt of Scotland during the 1870s. The formation of Hibernian FC in 1875 by impoverished Irish emigres living

in Edinburgh marked another departure from the game's  English upper middle class

origins. With the active support of the Catholic church, similar clubs sprang

up all over Scotland, wearing green and white to celebrate their Irish roots.

The sectarianism that was a feature of Scottish life quickly became apparent:

blue (usually navy), white and red are the colours of Unionism (and were the original colours of Hearts, for example) and became associated

with the Presbyterian establishment while green and white were universally adopted

by the clubs with roots in the poor Catholic minority. These sectarian affiliations

faded away over time with the notable exception of the intense rivalry between

Rangers and Celtic.

English upper middle class

origins. With the active support of the Catholic church, similar clubs sprang

up all over Scotland, wearing green and white to celebrate their Irish roots.

The sectarianism that was a feature of Scottish life quickly became apparent:

blue (usually navy), white and red are the colours of Unionism (and were the original colours of Hearts, for example) and became associated

with the Presbyterian establishment while green and white were universally adopted

by the clubs with roots in the poor Catholic minority. These sectarian affiliations

faded away over time with the notable exception of the intense rivalry between

Rangers and Celtic.

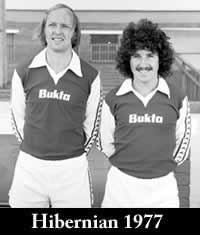

The first manufacturer of sports wear in the UK was Bukta who were established in 1879.

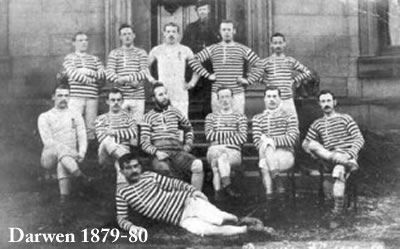

When Darwen, a team of cotton mill workers met the Old Etonians in the FA Cup semi-final of 1879, two worlds collided. Darwen were derided for wearing trousers cut off at the knee (held up by braces) instead of knickerbockers and a motley collection of shirts. The Darreners took the gentlemen-players from Eton to two replays before they were beaten, exhausted by working full shifts at the cotton-mills and repeated train journeys to London. Nevertheless this match is regarded as the turning point between the old establishment of gentleman-players and the new breed of working-class clubs emerging in Lancashire and the Midlands.

Players' tops were often described as "jerseys" (a close

fitting knitted garment without a collar) and occasionally as "guernseys"

(a heavier garment similar to a jersey and associated with fishermen). Burnley's tops in 1884 were described as blue and white "sarks," which means

a loose fitting chemise or shirt (with  collar). HFK associate Alick

Milne, has suggested that if players placed their nuts in an "Aldernay"

the association with the Channel Islands would be complete.

collar). HFK associate Alick

Milne, has suggested that if players placed their nuts in an "Aldernay"

the association with the Channel Islands would be complete.

Popular designs were self-coloured or hooped, (described as "striped"). Vertical stripes did not appear until circa 1883, when the term "shirts" appeared for the first time. It seems that the looms of the period were only capable of producing bolts of cloth with stripes running horizontally so that vertically striped garments could only be made by cutting the cloth "against the grain" and sewing the sections together. In 1887 the Rothwell Hosiery Company of Bolton introduced a novel machine that allowed stripes to be knitted in any direction. The popularity of vertically striped shirts mean that very quickly they became synonymous with Association Football.

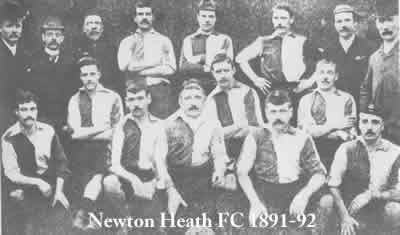

The term "quartered" was used to describe shirts or jerseys where the main body was made from four  separate panels, such as worn by Newton Heath (shown here) and Blackburn Rovers, a design which became known as "halved" in the 1890s. The term "harlequin" was used to describe the pattern we now call "quartered" (as worn most famously and much later by Bristol Rovers). This confusion of terms is not just a challenge to modern chroniclers: various contemporary sketches published in newspapers of the time portray teams wearing "quarters" when photographic evidence indicates they were "halved." Blackburn Rovers persisted in describing their halved shirts as "quartered" until the outbreak of World War Two.

separate panels, such as worn by Newton Heath (shown here) and Blackburn Rovers, a design which became known as "halved" in the 1890s. The term "harlequin" was used to describe the pattern we now call "quartered" (as worn most famously and much later by Bristol Rovers). This confusion of terms is not just a challenge to modern chroniclers: various contemporary sketches published in newspapers of the time portray teams wearing "quarters" when photographic evidence indicates they were "halved." Blackburn Rovers persisted in describing their halved shirts as "quartered" until the outbreak of World War Two.

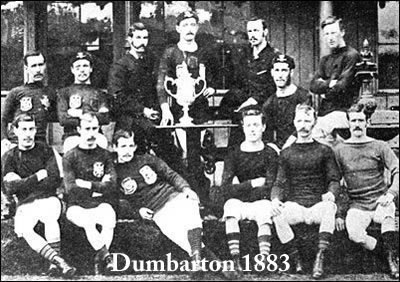

Players who were picked for their county or international team often had the appropriate badge sewn onto their jerseys. Recent research by HFK contributor Jim Jenkinson suggests that the Dumbarton players in this picture represented a Scottish Counties XI in  matches with the Glasgow, Birmingham, and Lancashire FAs (whose crests we believe they are sporting) while those in caps had recently played for the national team. If you refer back to the 1873-74 picture of Queen's Park above, you will notice that several capped players have the Scottish lion rampant crudely sewn onto their jerseys with swatches of the original navy jerseys.

matches with the Glasgow, Birmingham, and Lancashire FAs (whose crests we believe they are sporting) while those in caps had recently played for the national team. If you refer back to the 1873-74 picture of Queen's Park above, you will notice that several capped players have the Scottish lion rampant crudely sewn onto their jerseys with swatches of the original navy jerseys.

Over time the exotic colour combinations of the earliest era of organised English football began to disappear. I believe two factors were at work here, one practical and the other economic. The early rules made players in front of the ball "offside" (as in rugby football) and the game featured forwards who would dribble the ball towards their opponent's goal supported by a mob of players. Changes in the rules allowed players to pass the ball forward (a tactic pioneered by Queen's Park FC) making it essential that the player in possession could distinguish his colleagues from opponents. While multi-coloured shirts might look attractive as the players trot onto the pitch, they can be difficult to pick out on a gloomy winter afternoon, especially when covered with mud. It is interesting to note that rugby union clubs generally retained their multi-coloured shirts, perhaps because the offside rule means that only players behind the ball are in play (so there is less need to pick out a team mate at a distance or in front of play).

Economic factors were probably more significant. A survey

of Scottish clubs in the 1870s and early 1880s reveals that most clubs played

in plain jerseys (navy, red, maroon, green or rarely white) or narrow hoops

in a combination of two colours. Remember that players had to buy their

own kit in those days: the working class lads that took up the sport in Scotland would not

be inclined to join clubs that required expensive colour combinations associated

with public schools or universities that they had no connection with.

Economic factors were probably more significant. A survey

of Scottish clubs in the 1870s and early 1880s reveals that most clubs played

in plain jerseys (navy, red, maroon, green or rarely white) or narrow hoops

in a combination of two colours. Remember that players had to buy their

own kit in those days: the working class lads that took up the sport in Scotland would not

be inclined to join clubs that required expensive colour combinations associated

with public schools or universities that they had no connection with.

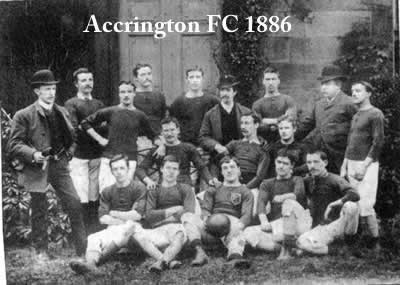

During the 1880s the balance of power in England shifted decisively from the upper middle class clubs of the south towards the industrial heartlands of the midlands and northwest. It is now thought that Darwen FC were the first to offer illicit inducements to Scottish players when they poached Fergie Suter, a stonemason who played for Partick Thistle after a friendly between the clubs in 1878. Suter was unable to continue his trade (the local stone in Lancashire being unworkable) but appeared to continue to live comfortably. The club denied paying him but Suter, disarmingly later said "I would interview the treasurer as occasion arose."

Rows over broken time payments, poaching, financial inducements or the offer of a job (with paid time off for training) became a serious issue and led in 1885 to a

decision by the FA to recognise professionalism in England. At the same time a lack of any formal structure to fixtures (which led to teams failing to show up if they could arrange a more lucrative fixture) was bringing the game into disrepute and undermining the need for the new professional teams to generate revenue.

The Football League was formed in 1888 to address this issue and provide the leading clubs with regular fixtures against each other. These clubs were controlled by self-made men with successful careers in the new industries of the late Victorian period and whose interest was in the potential of association football as a commercial venture. Grounds were enclosed so that turnstiles could be installed and spectators charged admission. As association football developed as a spectator sport, the importance of supporters being able to pick out their own team from a distance became evident, giving added impetus to the development of simple kits in contrasting, primary colours. One of the consequences of the introduction of professionalism in England was that the best players in Scotland were induced to move south to play for wages. The Scottish Football League was formed in 1890 but payments to players were not permitted in Scotland until 1893: even then most clubs could not afford to match the wages on offer in England and the drain of talent to the south remained a bone of contention well into the 1980s.

Once clubs became professional the expense of buying playing kits fell on the club rather than the players. Secretary-managers with an eye for the accounts naturally preferred to spend as little as possible reinforcing the trend towards simpler kits in basic colours.

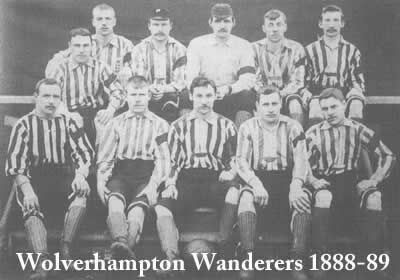

When Wolves travelled to Sunderland in September 1890, both the hosts and visitors turned out in red and white stripes. To avoid a repetition, clubs

When Wolves travelled to Sunderland in September 1890, both the hosts and visitors turned out in red and white stripes. To avoid a repetition, clubs  were instructed at the AGM of 1891 to register their colours for the following season, with a stipulation that

no two clubs could register the same colours. This cutting from the 11 July 1891 edition of the Burnley Express (click for a larger image) indicates that Stoke and Darwen were waiting to see what colours Burnley would register while Wolves adopted orange and blue to avoid clashing with Sunderland.

were instructed at the AGM of 1891 to register their colours for the following season, with a stipulation that

no two clubs could register the same colours. This cutting from the 11 July 1891 edition of the Burnley Express (click for a larger image) indicates that Stoke and Darwen were waiting to see what colours Burnley would register while Wolves adopted orange and blue to avoid clashing with Sunderland.

This rule was relaxed when the Second Division was added in 1892 and it became a requirement that each club should have a set of white tops to be worn when colours clashed (presumably teams that normally wore white had coloured alternatives.) The team that had been members of the Football League the longest was entitled to play in their regular strip. As a rule the home team changed when colours clashed.

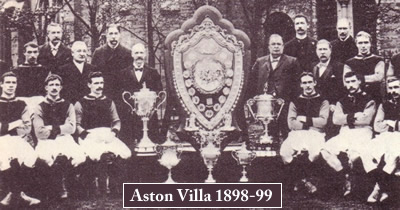

In 1891 Aston Villa wore claret jerseys with contrasting light blue sleeves and a distinctive neck band for the first time. Different shirts were adopted over the following two seasons before this style reappeared in 1894, remaining substantially unchanged for over 60 years. This combination was the first truly iconic football shirt and was widely copied.

Heavy shin guards were worn outside the socks. In England the colour of  stockings were not registered until the

turn of the century. Scottish FA records do,

however, record include "hose," which were usually self-coloured and

sometimes horizontally striped.

stockings were not registered until the

turn of the century. Scottish FA records do,

however, record include "hose," which were usually self-coloured and

sometimes horizontally striped.

Knickerbockers, which had to cover the knees were only available in white, black or navy blue (occasionally grey). It was not unusual for clubs to switch from one colour to another or indeed for players in the same team to wear differently coloured knickers. Some clubs registered their knickers simply as being "dark." Players called up for international duty were provided with a shirt by their FA but had to bring their own knickers and socks: HFK has evidence that the England team turned out in a mixture of white, navy and black knickers at least until 1897.

One of the difficulties of recording kits from this period is that until 1890, there was no requirement on clubs to register their colours with the Football League so we must rely on press coverage and other sources.

By the close of the century most of the leading clubs were wearing strips that would be recognisable today.

The Twentieth Century (1900-1939)

By 1904 the regulations that required footballers to cover their knees were

relaxed and shorts (still known as “knickerbockers” or "knickers")

became shorter. Shirts and shorts were close fitting and made from tough, heavyweight

natural fibres, usually cotton but sometimes wool. Socks were initially self-coloured but quickly design features such as contrasting

rings ("cadet stripes") on the turnover began to appear. The main stocking colour was always dark

(black or navy blue or, less frequently red or royal blue): pale colours did not

generally appear for another 50 years.

By 1904 the regulations that required footballers to cover their knees were

relaxed and shorts (still known as “knickerbockers” or "knickers")

became shorter. Shirts and shorts were close fitting and made from tough, heavyweight

natural fibres, usually cotton but sometimes wool. Socks were initially self-coloured but quickly design features such as contrasting

rings ("cadet stripes") on the turnover began to appear. The main stocking colour was always dark

(black or navy blue or, less frequently red or royal blue): pale colours did not

generally appear for another 50 years.

At the League AGM in 1904 (and again in 1906) the secretary of Liverpool FC put forward a proposal that would require every team in the competition to play in red shirts or jerseys and white knickers at home while visiting sides would wear white tops and dark knickers. The motion was defeated on both occasions.

At the League AGM in 1904 (and again in 1906) the secretary of Liverpool FC put forward a proposal that would require every team in the competition to play in red shirts or jerseys and white knickers at home while visiting sides would wear white tops and dark knickers. The motion was defeated on both occasions.

Knickers were still only available in white, black or navy blue (occasionally grey). It was exceedingly rare for clubs to wear matching shirts and shorts although Swansea Town (now Swansea City) have always worn all-white. Arsenal wore a change kit that featured matching shirts and shorts in dark blue.

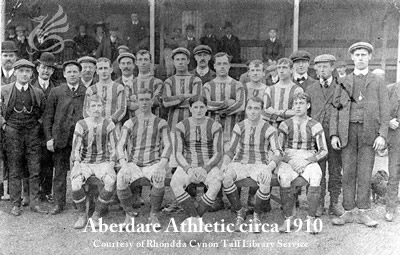

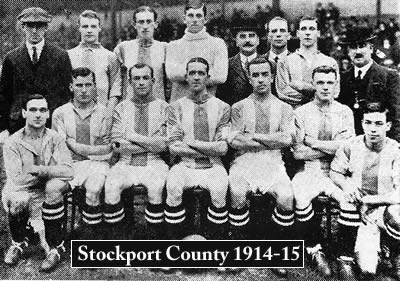

Shirts with laced crew necks appeared and became very popular in England (in Scotland buttoned crew necks were more common) but a variety of collar

designs were evident. Striped shirts were popular and the trend was for stripes

to become much wider, (typically 2"-3") than they had been during the previous century,  when 1" stripes were common. Not only were these broad stripes easier to see, they

tend to make the wearer appear taller while hoops emphasize the wearer's

bulk. This seems to be the reason why rugby teams favour hoops while soccer

clubs prefer vertical stripes. Although the 3" stripes worn by Aberdare (above) were the most common, other variants appeared such as those worn by Brentford (above) and Leeds City and the broad, 6" stripes adopted by Stockport County (left) just before the outbreak of World War One.

when 1" stripes were common. Not only were these broad stripes easier to see, they

tend to make the wearer appear taller while hoops emphasize the wearer's

bulk. This seems to be the reason why rugby teams favour hoops while soccer

clubs prefer vertical stripes. Although the 3" stripes worn by Aberdare (above) were the most common, other variants appeared such as those worn by Brentford (above) and Leeds City and the broad, 6" stripes adopted by Stockport County (left) just before the outbreak of World War One.

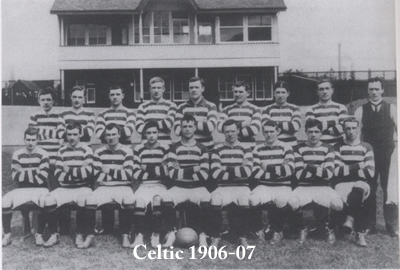

Stripes may have become closely identified with association football but hooped tops were not uncommon, particularly in Scotland, where

hoops of various widths became increasingly popular and remain so to this day. The 1" hoops that had  been popular before the introduction of vertical stripes continued to be worn by Queen's Park and East Stirlingshire but otherwise they began to disappear, replaced by 2" and 3" versions, such as those famously adopted by Celtic in 1903.

been popular before the introduction of vertical stripes continued to be worn by Queen's Park and East Stirlingshire but otherwise they began to disappear, replaced by 2" and 3" versions, such as those famously adopted by Celtic in 1903.

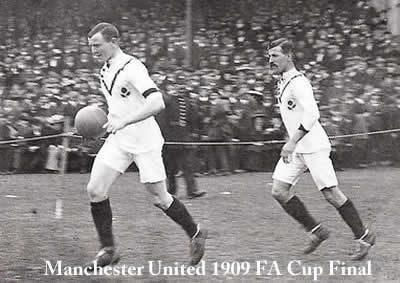

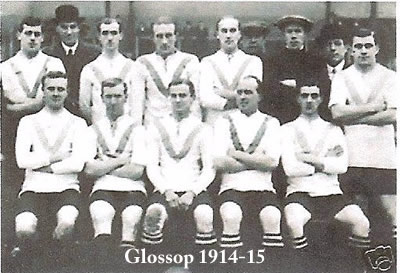

Novel designs that appeared in this period included

the bold V or chevron design, first worn by Manchester United in the 1909 FA Cup Final. This was one of the first truly original designs of the twentieth century later taken up Clapton Orient, Birmingham, Glossop and famously, Airdrieonians). Although these gradually faded from

fashion, the chevron design continued to be favoured by Rugby League clubs

in the north of England and has been revived on several occasions by, for example, Burnley and Scunthorpe United.

Although these gradually faded from

fashion, the chevron design continued to be favoured by Rugby League clubs

in the north of England and has been revived on several occasions by, for example, Burnley and Scunthorpe United.

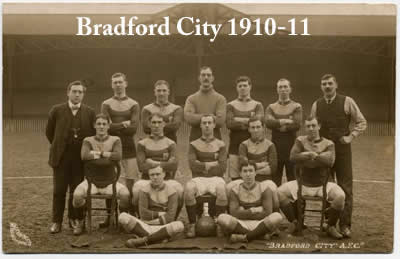

Yoked shirts

were first worn by Liverpool as a change kit and were notably worn by Bradford City when they won the FA Cup in 1911. This design proved rather less popular than the chevron, although they were adopted briefly by Motherwell and a few other clubs.

Pink and Salmon Pink gradually fell out of favour and disappeared by 1915. Shades of light blue continued to be popular. The reasons for this are obscure but we can speculate that pink was not considered sufficiently manly for the working men who both played and watched the game in ever growing numbers. Perhaps the English adage "pink for a girl and blue for a boy" has a wider application than what baby wears.

There are many challenges to the interpretation of photographs from the late Victorian and Edwardian era. Dyes were not colour fast, for example and kits would become very faded after a season of laundering. The photographic technology of the period was more sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum than other colours with the result that tones of blue tend to appear rather pale while reds and yellows appear relatively dark.

In 1909 goalkeepers in the Football League were required to wear distinctive tops so that match official could distinguish them in a scrum of players - previously they wore the same shirts as the outfield players. At first the rules stipulated that these be red or blue but within a few years, green was allowed and became the standard in England. In Scotland, goalkeepers generally wore deep yellow. There were no specially produced tops for 'keepers who normally wore heavy woollen sweaters, often teamed with flat caps to keep the sun out of their eyes.

In 1909 goalkeepers in the Football League were required to wear distinctive tops so that match official could distinguish them in a scrum of players - previously they wore the same shirts as the outfield players. At first the rules stipulated that these be red or blue but within a few years, green was allowed and became the standard in England. In Scotland, goalkeepers generally wore deep yellow. There were no specially produced tops for 'keepers who normally wore heavy woollen sweaters, often teamed with flat caps to keep the sun out of their eyes.

The Football League was suspended at the end of the 1914-15 season for the duration of the Great War. Some clubs continued to play with official sanction in order to boost civilian morale but were forbidden to pay players. The majority closed down for the duration and more than a few went out of business. In Scotland the First Division continued but the Scottish Second Division was suspended and it appears from Brian McColl's research that the members were disenfranchised around 1917.

HFK's contacts at the Victoria & Albert Museum have indicated that dyes from the Victorian and Edwardian periods generally came from Germany and the supply would have ceased with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. It follows that during and after the war, dyes were sourced from UK and other manufacturers and that the shades of some kits may have differed from the pre-war versions. Considerable caution has to be exercised in interpreting old black and white photographs, however, due partly to the technical problems of reproduction and because dyes were not colour fast in those days. After a long season of weekly boil washes, kits looked extremely washed out.

HFK's contacts at the Victoria & Albert Museum have indicated that dyes from the Victorian and Edwardian periods generally came from Germany and the supply would have ceased with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. It follows that during and after the war, dyes were sourced from UK and other manufacturers and that the shades of some kits may have differed from the pre-war versions. Considerable caution has to be exercised in interpreting old black and white photographs, however, due partly to the technical problems of reproduction and because dyes were not colour fast in those days. After a long season of weekly boil washes, kits looked extremely washed out.

When the Football League resumed in 1919 the First and Second Divisions were both extended from 20 to 22 clubs each. The following season the First Division of the Southern League was incorporated as associate members of the Football League to form Division Three. A year later the leading northern non-league sides were incorporated and the regional Third Divisions South and North were formed. The Scottish Football League also resumed in 1919 but without a Second Division. The surviving members formed a rebel Central League that proved such a threat that it was incorporated into the Scottish League structure in 1921.

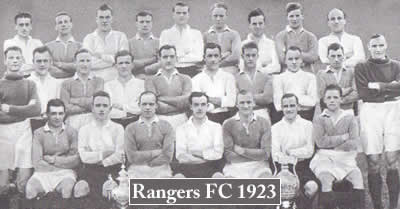

Bukta's domination as suppliers of football kits was challenged

by the formation of a new company in 1920, Humphrey Brothers

Clothing, which became in 1924 Umbro. There was little innovation in kit design during the 1920s although,

with both the English and Scottish leagues having expanded, there was considerably

more diversity. In Scotland, hooped tops in a variety of styles became more popular than ever.

Bukta's domination as suppliers of football kits was challenged

by the formation of a new company in 1920, Humphrey Brothers

Clothing, which became in 1924 Umbro. There was little innovation in kit design during the 1920s although,

with both the English and Scottish leagues having expanded, there was considerably

more diversity. In Scotland, hooped tops in a variety of styles became more popular than ever.

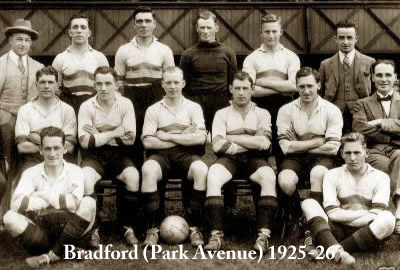

In 1921 the Football League ruled that the visiting club should change shirts in the event of a clash (previously the senior team retained their first choice kit when colours clashed): normally (and to save on the expense of having additional equipment), change shirts were worn with the usual shorts and stockings. Bradford (Park Avenue), who wore broad hoops in red, amber and black, adopted white change shirts with a broad band in the club colours, a kit that was identical to that worn by the Bradford Northern rugby league team.

Also in 1921 the International Football Association Board ruled that goalkeepers in international matches should wear deep-yellow jerseys. With sublime arrogance the FA delegate proposed that the jerseys should be red but this was rejected after a protest from the FA of Wales.

In 1927 the Scottish Football League's management committee decided that clubs should wear white shorts when at home, black when playing away. The reasons behind this bizarre rule are lost and it proved very unpopular with clubs and fans alike: there is some evidence that the more influential sides openly flouted the rule, which was rescinded at the SFL's Annual General Meeting in June 1929.

During the 1930s several innovations to kit design appeared. The

laced crew neck began to disappear in favour of collared shirts with a short

fly (a style that remained traditional in rugby union until quite recently). Everton added a stripe to the sides of their shorts in 1930, the first time that this style of trim had been seen in the twentieth century (it was not uncommon during Victorian times for teams to have a contrasting stripe sewn into the side of their knickerbockers).

During the 1930s several innovations to kit design appeared. The

laced crew neck began to disappear in favour of collared shirts with a short

fly (a style that remained traditional in rugby union until quite recently). Everton added a stripe to the sides of their shorts in 1930, the first time that this style of trim had been seen in the twentieth century (it was not uncommon during Victorian times for teams to have a contrasting stripe sewn into the side of their knickerbockers).

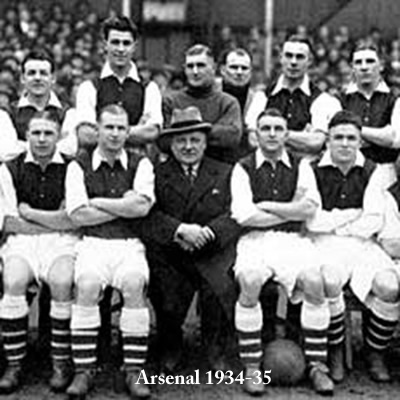

In 1933 Herbert Chapman introduced a radical new look to the Arsenal kit incorporating contrasting sleeves, navy stockings with narrow white hoops and a very large collar. Depending on which source you believe, Chapman either noticed someone at the ground wearing a red sleeveless sweater over a white shirt or played golf with famous cartoonist of the day Tom Webster who wore something similar. Although shirts with contrasting sleeves and even hooped stockings had all been seen before, the combination proved to be one of the most iconic kits of all time, making the Arsenal team instantly recognisable.

In the 1933 FA Cup final between Manchester City and Everton, numbers were worn on players' shirts for the first time: Everton's players were numbered 1-11 while City's shirts (pictured) went from 12-22. In 1939 numbers on the back of players' shirts became mandatory

in the Football League although Chapman's Arsenal had experimented with numbered shirts

earlier. Kit became more generously cut, giving rise to the baggy

shorts reaching to the knee so fondly remembered on shorter players.

In the 1933 FA Cup final between Manchester City and Everton, numbers were worn on players' shirts for the first time: Everton's players were numbered 1-11 while City's shirts (pictured) went from 12-22. In 1939 numbers on the back of players' shirts became mandatory

in the Football League although Chapman's Arsenal had experimented with numbered shirts

earlier. Kit became more generously cut, giving rise to the baggy

shorts reaching to the knee so fondly remembered on shorter players.

In 1939 the Football League and Scottish Football League were suspended following the outbreak of war with Nazi Germany.

The Post War Period (1946-1962)

Numbered shirts were first introduced in Scotland in 1946 but were not compulsory

until 1960. Celtic, rather quirkily, did not comply until 1960 and then insisted on wearing their numbers

on the players' shorts (and not on their shirts) until 1995.

Numbered shirts were first introduced in Scotland in 1946 but were not compulsory

until 1960. Celtic, rather quirkily, did not comply until 1960 and then insisted on wearing their numbers

on the players' shorts (and not on their shirts) until 1995.

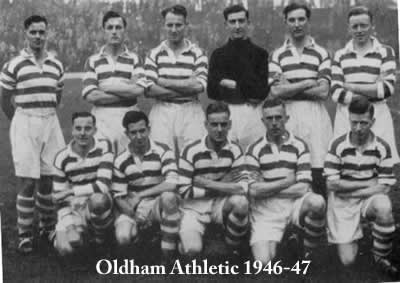

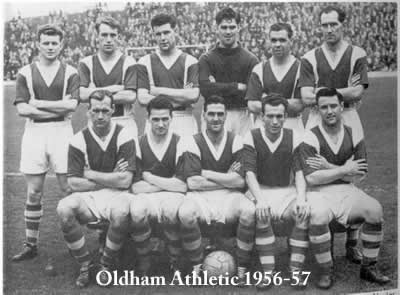

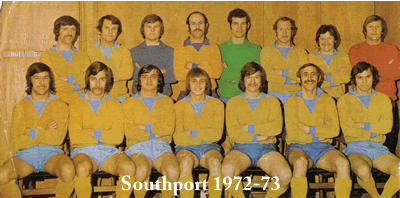

Clothing rationing immediately after the war limited the ability of clubs to replace their kits and several were forced to change from their traditional colours to those that they could purchase with ration coupons, which were often provided by supporters from their own personal rations. Southport FC turned out for several seasons in green and white hoops, a gift from one of the club’s directors made during the war; Oldham (pictured left) had to borrow a set of red and white hooped jerseys from the local rugby league club and West Brom wore plain blue. It appears that Clyde FC may have turned out in khaki shirts during 1946-47, although the reason for this is obscure and we have been unable to corroborate. Laced crew necks all but disappeared aside from a few die-hard traditionalist clubs in favour of collared shirts. Hooped stockings became extremely popular. During the early Fifties most clubs stuck to their traditional designs with only minor alterations to shirt and stocking trims.

In 1953 Bolton Wanderers played in the FA Cup Final in a novel

kit made from shiny material, the first time that artificial fabric had been

used in the manufacture of shirts and shorts. Torquay United and Queen's Park Rangers were among the

clubs to adopt this new style over the following seasons.

In 1953 Bolton Wanderers played in the FA Cup Final in a novel

kit made from shiny material, the first time that artificial fabric had been

used in the manufacture of shirts and shorts. Torquay United and Queen's Park Rangers were among the

clubs to adopt this new style over the following seasons.

The first predominantly pale stockings appeared in the early 1950s

and by the end of the decade white socks became widely available. Short sleeved shirts, which had first appeared in pre-war cup finals, turned up rather more regularly.

The first predominantly pale stockings appeared in the early 1950s

and by the end of the decade white socks became widely available. Short sleeved shirts, which had first appeared in pre-war cup finals, turned up rather more regularly.

Exposure to European football led to a dawning realisation that British football was perhaps not as superior as it had always been supposed. England’s 3-6 humiliation at Wembley by Hungary marked the beginning of a new era and over the rest of the decade, with Hibernian and Manchester United leading the way, clubs began to participate in European competition despite the initial hostility of the FA and SFA.

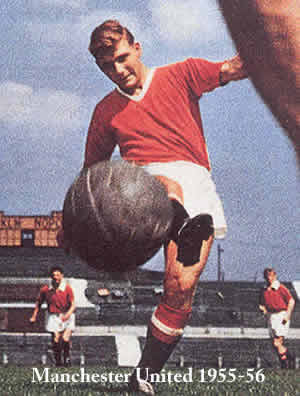

The debacle against Hungary may not have persuaded the English FA to review their antiquated approach to team selection and tactics but it did inspire Umbro to produce a new, streamlined kit which was first worn by the England team in November 1954. The "Continental" style, as it was called, featured sleek V necks instead of cumbersome collars, short sleeves and lightweight,  cotton shorts cut much shorter than the traditional style worn in the UK (many European sides had been wearing light weight shorts since before the war). These modern-looking strips caught on quickly with clubs and by 1957 almost every team in England and Scotland was wearing the new-look outfits.

cotton shorts cut much shorter than the traditional style worn in the UK (many European sides had been wearing light weight shorts since before the war). These modern-looking strips caught on quickly with clubs and by 1957 almost every team in England and Scotland was wearing the new-look outfits.

Rather sensibly, most Scottish clubs retained long sleeved versions of their shirts including old-fashioned collars to protect their players during the harsh winter months, wearing the Continental style during the warmer spells at the beginning and end of each season.

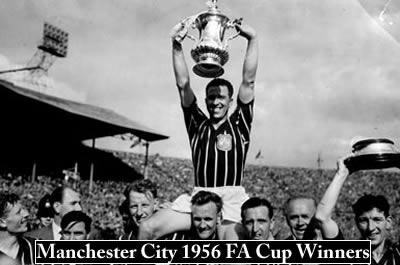

The new style of kit was generally matched with traditional designs, such as Oldham's much loved blue and white shirts but some innovative designs also appeared. Most notable of these was the candy striped shirt first worn by  Manchester City when they won the FA Cup in 1956. Aston Villa wore a similar top in light blue and claret when they won the Cup the following year. On both occasions, the teams had to wear change kits because of a clash of colours and took advantage of the situation to wear these novel shirts. (Although a glance back through this history will reveal that Brentford were wearing much the same sort of shirt at the turn of the century, proving that there is nothing new in shirt design.)

Manchester City when they won the FA Cup in 1956. Aston Villa wore a similar top in light blue and claret when they won the Cup the following year. On both occasions, the teams had to wear change kits because of a clash of colours and took advantage of the situation to wear these novel shirts. (Although a glance back through this history will reveal that Brentford were wearing much the same sort of shirt at the turn of the century, proving that there is nothing new in shirt design.)

Lightweight nylon stockings rapidly replaced the old heavy woolen versions and bulky shin pads became considerably lighter, reducing the familiar bulky outline. Boots also became considerably lighter and were now cut away from from the ankle, reducing support and protection while allowing greater agility and ball control.

The Sixties and Seventies (1962-1979)

Beginning around 1962, crew necks started to replace V-necks. Shirts became

ever tighter, shorts became very short indeed and stockings were lightweight. Long sleeves returned to fashion and were generally worn as they were designed rather than being rolled up to the elbow, as had been the fashion until the introduction of the Continental kits in 1955.

Beginning around 1962, crew necks started to replace V-necks. Shirts became

ever tighter, shorts became very short indeed and stockings were lightweight. Long sleeves returned to fashion and were generally worn as they were designed rather than being rolled up to the elbow, as had been the fashion until the introduction of the Continental kits in 1955.

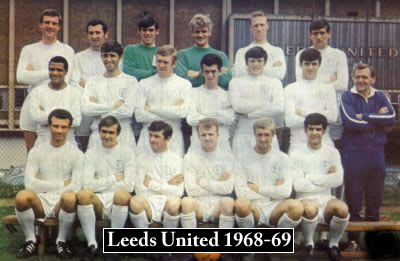

It might be supposed that technical advances in textile manufacture

and dye technology would have resulted in greater innovation in kit design.

The reverse was true. The Sixties was a period when tradition was unpopular

and sleek, simplified design in everything from furniture to fashion was the

norm. Plain kits looked better under floodlights, which now became universal

and allowed mid week games to be played at night. Floodlighting made white kits stand out  particularly well and there was a vogue for playing in all-white. Coventry started the trend in 1959 and during the following decade Tranmere, Bradford PA, Exeter, Brighton, Crystal Palace, Scunthorpe, Walsall, York, Doncaster, Port Vale and, most famously of all, Leeds United all dropped their traditional kits for white shirts and shorts. (The trend in Scotland was similar, with Dundee United, ES Clydebank, Morton and Stirling Albion all adopting white strips in this period.)

particularly well and there was a vogue for playing in all-white. Coventry started the trend in 1959 and during the following decade Tranmere, Bradford PA, Exeter, Brighton, Crystal Palace, Scunthorpe, Walsall, York, Doncaster, Port Vale and, most famously of all, Leeds United all dropped their traditional kits for white shirts and shorts. (The trend in Scotland was similar, with Dundee United, ES Clydebank, Morton and Stirling Albion all adopting white strips in this period.)

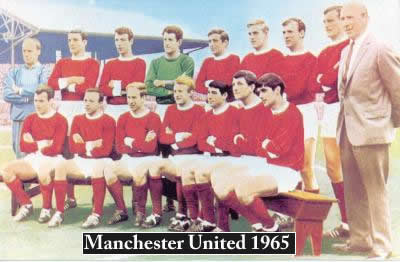

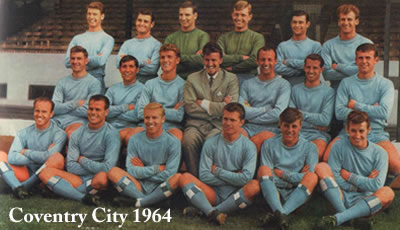

In 1962 Jimmy Hill, seeking to reinvigorate the under-achieving Coventry team launched his "Sky Blue Revolution" which included a smart all sky-blue kit for the players.

The idea was taken up by Chelsea (1963), Liverpool (1964) and Aberdeen (1966)

setting a trend that led to many well-loved traditional designs disappearing in favour of matching shirts and shorts, sometimes with contrasting stockings.

Traditional colours  were usually retained in the trimmings so Bradford (Park Avenue), for example retained green rings at the collar and cuffs while their neighbours, Bradford City, dropped their unique claret and amber stripes in favour of plain claret (1972-73) followed by all-amber (1973-74). A survey of kits worn around 1970 reveals a picture of drab uniformity.

were usually retained in the trimmings so Bradford (Park Avenue), for example retained green rings at the collar and cuffs while their neighbours, Bradford City, dropped their unique claret and amber stripes in favour of plain claret (1972-73) followed by all-amber (1973-74). A survey of kits worn around 1970 reveals a picture of drab uniformity.

In the 1960s clubs started to wear numbers on their shorts for the first time, an innovation started by Chelsea that became practically universal in the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1969 the Football League introduced a regulation banning navy blue shirts because, they alleged, these were too easily confused with match officials' black kit. (Teams were already not permitted to wear black shirts.) As a result Southend were forced to switch to navy and white stripes while Arsenal and Spurs both dropped their usual navy change tops in favour of yellow ones. No such concerns affected the Scottish Football League, where navy tops had been popular since the Victorian age and were, of course, the traditional colours of the national team.

That same season visiting English teams were required to change shorts and/or socks if they were deemed too similar to their opponents even if their shirts did not clash. This led, for example, to Arsenal sometimes playing in red shorts with their usual red and white "home" shirts, Everton wearing black or (later on) blue shorts and Liverpool wearing all white at Southampton and Sunderland. This unnecessary practice does not appear to have been enshrined in the rules but continues to be enforced in the Football League and (to a lesser extent) the English Premier League to this day. As a result teams now frequently commission home, away and third kits that can be mixed and matched while the big clubs will have alternative shorts and socks for each of their kit sets.

During the Seventies a reaction gradually set in as clubs began

to assert their individuality once more. In 1969, the manager of Aston Villa,

Tommy Docherty, introduced a radical redesign of the club’s traditional

strip featuring a collar with V inset. Within a few years almost every League

club was wearing similar collars.  (These had in fact first appeared in the mid

1950s and were worn by Hearts during the early 1960s but had not caught on.)

Many clubs returned to traditional themes. Bristol Rovers, for example dropped their plain blue shirts and once again played in the traditional quartered shirts that made them immediately identifiable. Huddersfield Town and Sheffield Wednesday who had also "modernised" their appearance with plain blue shirts (in Wednesday's case with smart white sleeves) returned to the blue and white stripes that they had worn since time immemorial.

(These had in fact first appeared in the mid

1950s and were worn by Hearts during the early 1960s but had not caught on.)

Many clubs returned to traditional themes. Bristol Rovers, for example dropped their plain blue shirts and once again played in the traditional quartered shirts that made them immediately identifiable. Huddersfield Town and Sheffield Wednesday who had also "modernised" their appearance with plain blue shirts (in Wednesday's case with smart white sleeves) returned to the blue and white stripes that they had worn since time immemorial.

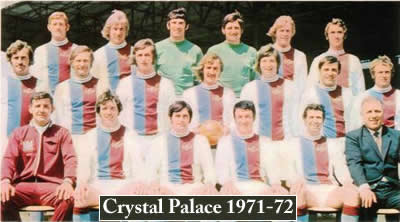

Several clubs went a step further and introduced novel variations on their traditional colours that again made them instantly recognisable. Crystal Palace, a club never shy of experimenting, introduced a wonderful white strip with broad claret and light blue panels in 1971. Birmingham City introduced  their much-loved "penguin strip" that same year while Carlisle made their debut in the First Division in 1974 wearing a similar outfit but with red trim on each side of the white panel. Also in 1974 Burnley added a dramatic V to their plain claret shirts.

their much-loved "penguin strip" that same year while Carlisle made their debut in the First Division in 1974 wearing a similar outfit but with red trim on each side of the white panel. Also in 1974 Burnley added a dramatic V to their plain claret shirts.

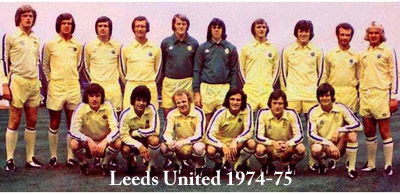

In 1973 Leeds’ manager Don Revie, a man with an eye for a gimmick with a commercial application, entered into a deal with

a brand new kit manufacturer, Admiral, that would lead to a revolution in kit design with far-reaching effects. Admiral's proposal was to redesign the club's kit in such a way that the result could be copyrighted and replicas sold to the general public, with the club receiving a royalty for each replica sold. The new Leeds kit was practically identical to the Umbro version that preceded it with only the Admiral logos to  distinguish it. Admiral's stroke of genius was to create a radically different change kit in all-yellow with blue and white trim, which Leeds wore in all their away games, regardless of whether the home team's kit clashed with Leeds' white. The term "change kit" was rapidly replaced with the misnomer "away kit," which has now become universal as a result.

distinguish it. Admiral's stroke of genius was to create a radically different change kit in all-yellow with blue and white trim, which Leeds wore in all their away games, regardless of whether the home team's kit clashed with Leeds' white. The term "change kit" was rapidly replaced with the misnomer "away kit," which has now become universal as a result.

Admiral pursued a vigorous and innovative marketing campaign, targeting the

top clubs, radically redesigning their kits for showcase events to ensure maximum exposure. Manchester United switched to Admiral in 1975, followed by West Ham and Southampton in 1976, both of whom unveiled their new Admiral strips in important cup finals. The new concept quickly caught on and while kits supplied to the clubs were well made, using natural fibres and  embroidered detailing, those sold to the public were manufactured as cheaply as possible in nylon with heat-applied plastic logos that broke up after a few washes. These cheaply made replicas were sold at two or three times the price of the generic copies that preceded them and became must-have items for the nation's young fans, proudly worn on the school playing field and at the weekend kick about in the park.

embroidered detailing, those sold to the public were manufactured as cheaply as possible in nylon with heat-applied plastic logos that broke up after a few washes. These cheaply made replicas were sold at two or three times the price of the generic copies that preceded them and became must-have items for the nation's young fans, proudly worn on the school playing field and at the weekend kick about in the park.

Around this time the Football League introduced a rule that away teams should change their shorts and/or stockings if these clashed with those of the home team. Everton, for example, often played in blue shorts while Manchester United wore black shorts with their red shirts when the occasion demanded.

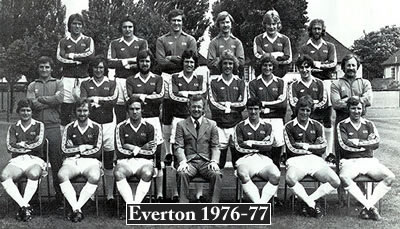

The established manufacturers, Umbro

and Bukta, responded to Admiral's challenge in 1976 with the introduction of a new range of kits featuring their own logos incorporated into the trim on the sleeves, shorts and stockings (Admiral also launched a similar range) as well as ensuring their trademarks appeared prominently on the chest.

The established manufacturers, Umbro

and Bukta, responded to Admiral's challenge in 1976 with the introduction of a new range of kits featuring their own logos incorporated into the trim on the sleeves, shorts and stockings (Admiral also launched a similar range) as well as ensuring their trademarks appeared prominently on the chest.

While Admiral challenged Umbro and Bukta for contracts with the leading teams, a new wave of sportswear manufacturers seized the opportunity to court clubs lower down the leagues. One of the first was Hobott who redesigned Sheffield United's kit after the Blades dropped into the Third Division in 1979 (presumably Admiral, who had provided their previous kits lost interest) and went on to pick up contracts with many lower league clubs in England. The giant German sportswear manufacturer, Adidas, who enjoyed a near monopoly in Europe, appeared on the English scene in 1977 when they supplied Ipswich Town and Middlesbrough with their iconic three-stripe trim kit.

Towards the end of the 1970s there was increasing pressure on

clubs to feature sponsor’s logos on player’s shirts, pressure that

was resolutely resisted by the football and broadcasting authorities. The first ever sponsorship deal involved West German team, Eintracht Braunschweig who wore the Jägermeister logo type on their shirts in 1973. The first shirt sponsorship deal among the UK's senior clubs was brokered by former Wolves striker Derek Dougan, who joined joined Kettering Town, then in the Southern League, as chief executive after he retired. Within a month he brokered a deal with a local company, Kettering Tyres, whose name appeared on the players' shirts in a match against Bath City on January 24 1976. Four days later the Football Association ordered the sponsorship be removed.

Dougan removed only the final letters, changing the wording on the shirts to "Kettering T" and claimed this was nothing to do with their sponsors but simply the name of the club. In April 1976 the FA ordered the wording removed under the threat of a £1,000 fine.

Kettering, along with Derby County and Bolton Wanderers then submitted a proposal to the FA to allow shirt sponsorship, which was accepted on June 3 1977. Kettering were, however, unable to find a sponsor for the following season.

In 1977 Hibernian became the first top-level UK club to wear shirts carrying sponsorship (by Bukta, the kit manufacturer). Derby County landed the first English deal with Saab in 1978 but the sponsored shirts were never worn after the pre-season photo shoot. It fell to Liverpool a year later to wear the first shirts to carry a sponsor’s name in the Football League in 1979.

The Eighties – The Market Rules (1980-1989)

Once Hibs and Liverpool broke the mould clubs began to exploit the potential

revenue from selling shirt sponsorship. The BBC and ITV companies refused to

broadcast matches featuring sponsored shirts, forcing clubs to remove sponsors’

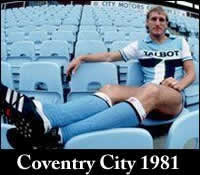

logos when the cameras were present. Coventry City thought they were on a winner

when they introduced a kit that incorporated the logo of the Talbot car manufacturing

company into their design but the TV companies boycotted them until they introduced

an alternate strip for televised games.

Once Hibs and Liverpool broke the mould clubs began to exploit the potential

revenue from selling shirt sponsorship. The BBC and ITV companies refused to

broadcast matches featuring sponsored shirts, forcing clubs to remove sponsors’

logos when the cameras were present. Coventry City thought they were on a winner

when they introduced a kit that incorporated the logo of the Talbot car manufacturing

company into their design but the TV companies boycotted them until they introduced

an alternate strip for televised games.

In 1983 the broadcasters finally gave way and allowed sponsored

shirts to be shown: immediately the value of a sponsorship deal with a club

that would feature regularly on Match of the Day or the equivalent ITV programmes

went through the roof. At the time, Football League regulations restricted the

size of logos to a maximum of 81 square centimeters (32 square inches) but for

televised games they had to be half this size.

In 1983 the broadcasters finally gave way and allowed sponsored

shirts to be shown: immediately the value of a sponsorship deal with a club

that would feature regularly on Match of the Day or the equivalent ITV programmes

went through the roof. At the time, Football League regulations restricted the

size of logos to a maximum of 81 square centimeters (32 square inches) but for

televised games they had to be half this size.

Adidas made considerable inroads into the increasingly competitive kit provider market, capturing important contracts with Manchester United (1980) and Liverpool (1985) as well as many smaller clubs.

Traditional cotton shirts were replaced by artificial polyester fabrics: from the manufacturers' point of view these were not only cheaper, lighter and less moisture absorbent but also could be processed through a novel process of dye sublimation. This allowed colours and complex patterns to be applied with heat to the basic fabric in a manner not possible with natural fabrics and led to a design revolution.

The new polyester kits became increasingly intricate as more manufacturers became involved with an eye for the developing replica kit market. French manufacturer Le Coq Sportif introduced pinstripes on Chelsea's 1981-82 shirts while Spall created a similar design for Blackburn Rovers' yellow change kit. The French company went on to introduce some truly elegant designs for Everton, Aston Villa and Portsmouth and can be credited with creating  the definitive 1980s design feature, the shadow stripe which was first worn by Tottenham Hotspur in 1982-83.

the definitive 1980s design feature, the shadow stripe which was first worn by Tottenham Hotspur in 1982-83.

A third colour was introduced to the strips of most clubs: Liverpool, for example, who had introduced yellow to their kit in 1976, featured pale gray trim in the mid-1980s and later dark green.

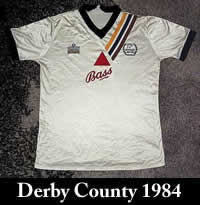

A number of clubs celebrated their centenaries during the decade and one of these, Derby County, introduced special kit to celebrate the occasion in 1984, establishing a precedent that would become the norm some 20 years later.

The monopoly enjoyed by Umbro and Bukta enjoyed since time immemorial

was now broken as a new breed of kit manufacturers stepped in with sophisticated

new brands. Le Coq Sportif (France), Adidas (Germany), Patrick, Matchwinner

and Hobott (UK) captured significant sections of the market that now included

selling replica kits to fans. Following the success of the Danish team in the 1986 World Cup, their kit supplier Hummel, made significant inroads in England supplying versions of their distinctive and complicated halved designs to Southampton, Coventry and Aston Villa. This design soon fell out of favour but Hummel's distinctive chevron sleeve trim remained prominent.

The monopoly enjoyed by Umbro and Bukta enjoyed since time immemorial

was now broken as a new breed of kit manufacturers stepped in with sophisticated

new brands. Le Coq Sportif (France), Adidas (Germany), Patrick, Matchwinner

and Hobott (UK) captured significant sections of the market that now included

selling replica kits to fans. Following the success of the Danish team in the 1986 World Cup, their kit supplier Hummel, made significant inroads in England supplying versions of their distinctive and complicated halved designs to Southampton, Coventry and Aston Villa. This design soon fell out of favour but Hummel's distinctive chevron sleeve trim remained prominent.

Admiral, who had done so much to transform kits in the previous decade over-extended themselves and entered financial administration, although the brand re-emerged later in the decade under new ownership.

Towards the end of the decade shirts became more generously cut as the new lightweight fabrics became widely available. Shirts were produced with both short and long sleeves and players could choose which to wear (unless they played for Arsenal, where the captain decided if the team would play in long or short sleeves). Improvements in the dye sublimation process allowed for intricate designs to be printed into the fabric itself, permitting manufacturers to counteract the burgeoning market in cheap counterfeit kits that had begun to appear.

The Nineties (1990-2000)

During the '90s football was transformed as the old terraces were swept away and huge amounts of cash were injected into top-flight football through lucrative deals with satellite TV companies. The introduction of all-seat stadia and increased admission charges finally reduced the problem of hooliganism that had plagued the game over the previous decade and the fall in attendances that had begun in the 1960s was reversed. The marketing of replica kits, which reflected a new era of brash confidence, now exploded and everyone who considered him or

her self to be a supporter expected to turn out on match day wearing the

current replica kit. Shirts had to look good not only on the pitch but also

when worn with jeans. Artificial fabrics were now universally used, with manufacturers vying with each other every season to extol the remarkable properties of their latest miracle fabric.

During the '90s football was transformed as the old terraces were swept away and huge amounts of cash were injected into top-flight football through lucrative deals with satellite TV companies. The introduction of all-seat stadia and increased admission charges finally reduced the problem of hooliganism that had plagued the game over the previous decade and the fall in attendances that had begun in the 1960s was reversed. The marketing of replica kits, which reflected a new era of brash confidence, now exploded and everyone who considered him or

her self to be a supporter expected to turn out on match day wearing the

current replica kit. Shirts had to look good not only on the pitch but also

when worn with jeans. Artificial fabrics were now universally used, with manufacturers vying with each other every season to extol the remarkable properties of their latest miracle fabric.

The leading clubs faced increasing criticism for exploiting their fans by changing strips too frequently. As a result of this pressure, several top clubs entered into a voluntary agreement to retain their kits for two seasons. By the end of the decade clubs were required to include a “sell by” date but managed to subvert the spirit of the agreement by introducing "third kits" and rotating the introduction of new strips every season.

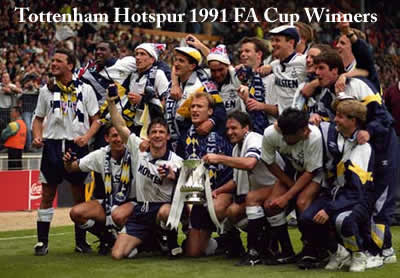

In the FA Cup final of 1991 Tottenham Hotspur once again set

a trend by turning out in long, baggy shorts. Many sniggered at the time but

within no time at all, every team in the England and Scotland was turning out

in similar kit.

In the FA Cup final of 1991 Tottenham Hotspur once again set

a trend by turning out in long, baggy shorts. Many sniggered at the time but

within no time at all, every team in the England and Scotland was turning out

in similar kit.

In 1991 Adidas launched a re branding exercise and introduced their new range of sportswear under the Adidas Equipment brand. The iconic three stripe trim disappeared and was replaced by three very large contrasting stripes that were  incorporated in various ways in (for example) Liverpool's kits between (1991-1995) and Arsenal's 1993 away kit. These attracted considerable criticism from fans who thought this corporate branding overwhelming and it was quietly dropped after 1995.

incorporated in various ways in (for example) Liverpool's kits between (1991-1995) and Arsenal's 1993 away kit. These attracted considerable criticism from fans who thought this corporate branding overwhelming and it was quietly dropped after 1995.

The launch of the (English) Premier League in 1992 and the decision by the FA to drop their ban on clubs wearing black (referees now wore tops in a variety of colours chosen to avoid clashing with either team's colours) led to a vogue for all-black change strips, with Manchester United leading the way in 1993. Clubs were loath to alienate their supporters by making radical changes to their traditional colours but there was no such inhibition over the choice of change kits. A bewildering range of novel colours schemes came into vogue that included such esoteric shades as "ecru" (pale beige), powder blue, silver gray, purple, lilac, jade, bottle green and even "denim."

The Premier League pioneered the addition of sleeve patches: these are now routinely added to shirts for domestic and international competitions. Player's names were first printed on the back of players' shirts after the Premier League was launched in 1992, a smart marketing move, as fans could now pay for the privilege of having their idol's name - or indeed their own - printed on their expensive new replica shirts. These details not only add value to replica kit sales but also make the acquisition of match worn shirts more desirable, feeding the black market in counterfeit sales. (HFK counsels all would be collectors to check with a reliable authority before bidding for items on e-bay.)

Manufacturers also pushed the boundaries in their designs for "home" kits, while generally keeping to traditional colour schemes. Abstract patterns, splotches, scratch marks, barcode stripes and (in the case of West Brom), wavy stripes all appeared. Influence, a company owned by Birmingham City's owners launched a number of outrageous designs including the infamous "paint box strip" worn by Birmingham in

Manufacturers also pushed the boundaries in their designs for "home" kits, while generally keeping to traditional colour schemes. Abstract patterns, splotches, scratch marks, barcode stripes and (in the case of West Brom), wavy stripes all appeared. Influence, a company owned by Birmingham City's owners launched a number of outrageous designs including the infamous "paint box strip" worn by Birmingham in  1992, which featured yellow, navy and green splashes all over plain blue shirts and shorts.

1992, which featured yellow, navy and green splashes all over plain blue shirts and shorts.

Alongside the new wave of increasingly intricate designs came a vogue for generously cut retro strips. Manchester United introduced a change kit in 1992 based on the colours of their former incarnation, Newton Heath while Aston Villa revived the hooped neck style worn first a century before.

Stockings, long considered a minor adjunct, now became integral to the overall design concept, with club monogrammes, badges and manufacturers' logos added along with various trims.

The American sportswear giant Nike entered the market in 1993 when they replaced Adidas as Arsenal's kit supplier, offering designs that were carefully contrived and individual, at least for the leading clubs. Umbro fought hard to maintain their market share introducing all sorts of novel motifs and designs. Lower down the  leagues, clubs had either to settle for a standard template from one of the big manufacturers or sign deals with one of the smaller, emerging companies. A few clubs designed and marketed replica kits under their own brand names (including Oxford United, shown here) but the economics rarely worked

leagues, clubs had either to settle for a standard template from one of the big manufacturers or sign deals with one of the smaller, emerging companies. A few clubs designed and marketed replica kits under their own brand names (including Oxford United, shown here) but the economics rarely worked  for long, the big players being able to offer deals that undercut those of small manufacturers because of the economies of scale they enjoyed, not least because they had shifted their manufacturing plants to the Far East where labour costs were a fraction of those in the European Union.

for long, the big players being able to offer deals that undercut those of small manufacturers because of the economies of scale they enjoyed, not least because they had shifted their manufacturing plants to the Far East where labour costs were a fraction of those in the European Union.

Overall, the 1990s will be remembered as a pivotal period in the design of kits. While the extravagant designs, excessive detailing and general clutter of the period now look out of date, shirts from this period have become extremely collectible.

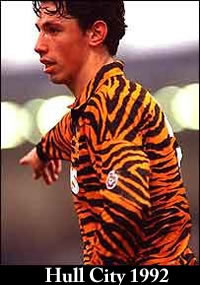

We cannot leave the decade without mentioning the extraordinary tiger-print shirts worn by Hull City during this period, without question the most outrageous design worn by any club anywhere at anytime.

Towards the end of the decade styles became more minimal and the emphasis was on the technology of the material as much as the design. Reversed seams appeared for a more comfortable fit without rubbing the skin while lightweight, hi-tech fabrics promised to keep the wearer cool (or warm) and draw moisture away from the body. Each company introduced its own new fabric, enhanced with mesh panels, integral undershirts and other features that would enable peak performance, or so it was claimed. Quite what the advantage of these "revolutionary" concepts remains unproven. Most top level players wore "foundation garments," negating any claims for the capacity of shirts to improve athletic performance. One manufacturer has told HFK, when asked about these miracle fabrics, "it's all polyester and comes from the same source - it's all crap."

The New Millennium - Sanity Restored but Prices Fixed

The trend for simpler designs continued with subtle piping and plain trim at

collar and cuff. Kappa’s body hugging Kombat range made its appearance

in 2002 when it was worn by Tottenham Hotspur (inevitably). The skin tight Lycra

outfit was intended to emphasise the physique of the players but proved less

popular with fans whose body shape was more influenced by consumption of pies

and beer.

The trend for simpler designs continued with subtle piping and plain trim at

collar and cuff. Kappa’s body hugging Kombat range made its appearance

in 2002 when it was worn by Tottenham Hotspur (inevitably). The skin tight Lycra

outfit was intended to emphasise the physique of the players but proved less

popular with fans whose body shape was more influenced by consumption of pies

and beer.

The marketing of replica kits attracted the attention of the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) in 2003 whose investigation upheld allegations of price fixing between top clubs, manufacturers and sportswear retailers who had entered into agreements that prevented the big supermarket chains from selling replica kits at discount prices. The manufacturers, clubs and sportswear retailers contrived to protect their position and maintain high prices while excluding discount sellers in direct defiance of the OFT's decision and continue to do so.

The marketing of replica kits attracted the attention of the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) in 2003 whose investigation upheld allegations of price fixing between top clubs, manufacturers and sportswear retailers who had entered into agreements that prevented the big supermarket chains from selling replica kits at discount prices. The manufacturers, clubs and sportswear retailers contrived to protect their position and maintain high prices while excluding discount sellers in direct defiance of the OFT's decision and continue to do so.

In 2003 Puma, now a major player in the global football kit market, designed a dramatic asymmetrical design for Fulham, a trend that was taken up by other clubs the following season. Another design innovation was the introduction of the 360 degree concept, with features that can only be appreciated from the back of the strip. This trend was reinforced by regulations that required the numbers and names on the back of shirts to be printed on a solid background. As a result striped and hooped shirts were usually designed with a single solid coloured panel on the back.

Novel trimmings appeared on stockings in a variety of patterns, which included vertical stripes down the side, bands that curved round the back and contrasting reverses.

Novel trimmings appeared on stockings in a variety of patterns, which included vertical stripes down the side, bands that curved round the back and contrasting reverses.

In 2006-07 the Football League permitted secondary sponsors' logos to appear on the back of player's shirts and shorts (the Premier League did not follow suit) while in Scotland secondary sponsorship was permitted on shorts as well.

For the majority of clubs existing on

modest means, the annual or bi-annual introduction of new kits was a balancing

act between generating revenue and alienating their loyal fan base. More than

one deal was scuppered because the new design was disliked by fans or because

demand outstripped supply. A welcome trend was for fans to be involved

in the design process. Manufacturers recognise that involving their potential

customers has commercial advantages while clubs now frequently consulted their

fans when choosing next season’s design. The dynamics of the market mean, however, that even the best designs, such as Le Coq Sportif's stunning Carlisle United offering have a maximum life of two seasons.

For the majority of clubs existing on

modest means, the annual or bi-annual introduction of new kits was a balancing

act between generating revenue and alienating their loyal fan base. More than

one deal was scuppered because the new design was disliked by fans or because

demand outstripped supply. A welcome trend was for fans to be involved

in the design process. Manufacturers recognise that involving their potential

customers has commercial advantages while clubs now frequently consulted their

fans when choosing next season’s design. The dynamics of the market mean, however, that even the best designs, such as Le Coq Sportif's stunning Carlisle United offering have a maximum life of two seasons.

Every season, manufacturers vied with each other to introduce the

latest design innovation and new strips were often showcased in the last match

of the previous season. For the top clubs like Manchester United, Chelsea,  Liverpool and Arsenal, sales of replica kits world-wide now created annual revenue streams

of tens of millions of pounds sterling. At the other end of the scale, East Stirlingshire's hopes of reviving their traditional one inch hooped shirts in 2008 ran into the sand because the only companies prepared to manufacture them insisted on pre-sale guarantees that far exceeded what this impoverished Scottish Third Division club could offer. The big manufacturers courted the leading clubs with lucrative deals and exclusive designs while clubs in the lower leagues had to scratch around for contracts with lesser players such as Vandanel and Carlotti. That being said, these smaller manufacturers made every effort to introduce new templates each season. Notable among these was the Italian company, Errea, who emerged in 1994 with a long standing deal with Middlesbrough and who specialised in producing bespoke kits for smaller clubs with very Italian flair for design.

Liverpool and Arsenal, sales of replica kits world-wide now created annual revenue streams

of tens of millions of pounds sterling. At the other end of the scale, East Stirlingshire's hopes of reviving their traditional one inch hooped shirts in 2008 ran into the sand because the only companies prepared to manufacture them insisted on pre-sale guarantees that far exceeded what this impoverished Scottish Third Division club could offer. The big manufacturers courted the leading clubs with lucrative deals and exclusive designs while clubs in the lower leagues had to scratch around for contracts with lesser players such as Vandanel and Carlotti. That being said, these smaller manufacturers made every effort to introduce new templates each season. Notable among these was the Italian company, Errea, who emerged in 1994 with a long standing deal with Middlesbrough and who specialised in producing bespoke kits for smaller clubs with very Italian flair for design.

Most clubs and certainly all of the members of the English Premier League, now had three kits each season, their "Home," "Away" (ie change) and "Third" kits with additional sets of shorts and stockings for each kit so that they had a bewildering assortment available. Match officials had the last word on what teams could wear and, encouraged by increasing interference from the national authorities, they insisted that away teams  change shorts and/or socks when there was even a minimal clash with their home opponents. This unwelcome trend resulted in all sorts of nonsensical changes being forced on teams, such as Aston Villa having to dig out a set of white shirts when they entertained West Ham in April 2009 because the referee did not like the fact the both teams would wear sky blue sleeves.

change shorts and/or socks when there was even a minimal clash with their home opponents. This unwelcome trend resulted in all sorts of nonsensical changes being forced on teams, such as Aston Villa having to dig out a set of white shirts when they entertained West Ham in April 2009 because the referee did not like the fact the both teams would wear sky blue sleeves.

Some clubs retained each kit for two seasons and replaced one of them every year, so that last season's "Away" kit became this season's "Third" kit. However, when a contract with a manufacturer ended, the new contractor would introduce a brand new suite of kits, thus ensuring that there was always something for the fan to spend money on. New designs were frequently showcased in the final matches of each season and appeared in club shops over the summer.

spend money on. New designs were frequently showcased in the final matches of each season and appeared in club shops over the summer.

Special anniversary kits were introduced such as Charlton Athletic's 2004 centenary kit and, with permission from the relevant league authorities, were worn on one or two occasions: replicas were then sold as limited editions to fans at premium prices. Some clubs took a different approach and revived early kits; Rochdale wore a recreation of their original black and white striped kit during 2007-08 for example while Norwich City wore a recreation of the strip worn in their famous 1959 FA Cup run in their third round tie in 2009 while the two Manchester clubs wore special commemorative strips when they met in February 2008 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Munich disaster. From 2007-08 clubs in England and Scotland have worn poppies printed on their shirts in matches played over the weekend of Remembrance Sunday.

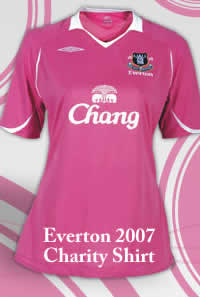

In 2007 Everton launched a special edition pink shirt in support of Breast Cancer  Research. This shirt was never worn on the pitch but the idea proved so popular a second edition was launched the following year and several clubs followed suit by producing special edition shirts with proceeds going to charity. Aston Villa went one step further by donating their shirt sponsorship to Acorns Children's Hospice, sparking a trend for similar arrangements in England and Scotland.